|

|

|

Schnitzler: Story: Spheres

Sphere Title

Info

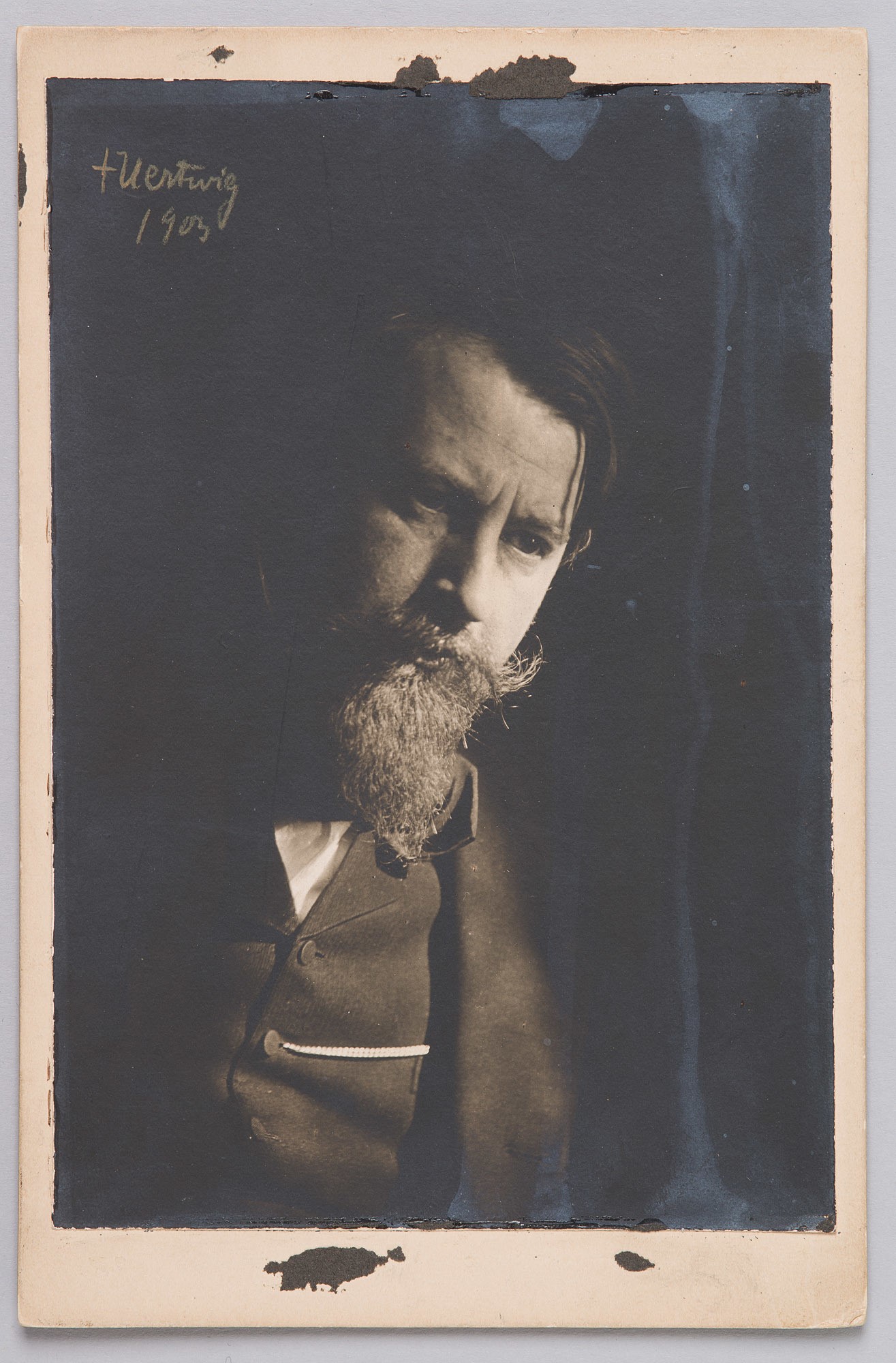

Arthur Schnitzler 1903, Source: Theatermuseum, Wien

Arthur Schnitzler 1903, Source: Theatermuseum, Wien

Schnitzler: Story: Spheres

An interactive essay

Stories and dramas are made of words, people and places. The Schnitzler Spheres are a network of 360 degree spherical photos, which combine the words, people and places behind the life and works, the stories and dramas, of the Viennese writer Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931).

Stories and dramas need time, but also space. Schnitzler spent most of his life in Vienna. It was the city of his birth and the city of his imagination, a place filled with his literary creations. Figures whose storylines crossed and re-crossed the tracks of their author’s own life, both within Vienna and radiating from it.

The Schnitzler Spheres show the special places at which Schnitzler’s life and imagination intersected: the Anatomical Theatre where he studied medicine, the Burgtheater, which saw a number of his plays premiered, his holiday destination the Südbahnhotel, the puppet theatre in the Prater amusement park, and the organisational hub of the Ringstraße, where Vienna did its business.

The Schnitzler Spheres are conceived as a kind of visual echo chamber for key themes in the author’s life and works. They create a mental map, linking parts of his creative and private life, like synapses link regions of the human brain. This thinking in spaces is known as psycho-topography.

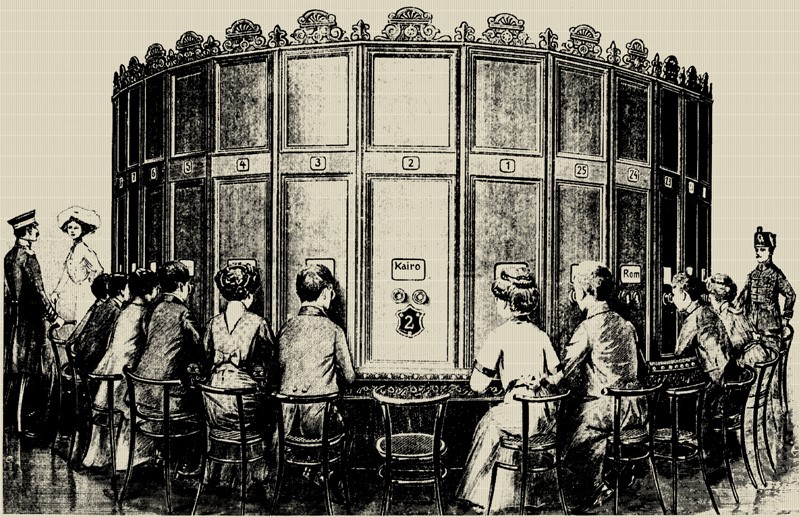

The sphere is used as the central organising principle as it matches Schnitzler’s own thought patterns. Just as Vienna is built around the Ringstraße, so the circle and the circular are a recurring theme in Schnitzler’s works. Thus, the play Reigen (La Ronde, or Round Dance) consists of ten interlocking scenes between pairs of lovers in and around Vienna. Each of its ten characters appears in two consecutive scenes (with one from the final scene, The Prostitute, having appeared in the first, taking it back full-circle). The circular spectacle presents scenes from a panorama of Vienna around 1900. In his diary Schnitzler records over 200 visits to a Kaiserpanorama. This was a very popular progenitor of cinema in which the customers sat at viewing stations arranged around a circular structure. They looked through a pair of lenses showing a round of stereoscopic glass slides of places and events, both local and global.

Kaiserpanorama August Fuhrmann 1880

Kaiserpanorama August Fuhrmann 1880

Another circular attraction in Schnitzler’s work, found like the Kaiserpanorama in the Prater, and another model for the psycho-topographic logic of the spheres is the merry-go-round or ‘Ringelspiel’, as Andrew Webber explains in one of the hotspots in the ‘Börse’ or Stock Exchange sphere, where it is linked to Vienna’s representative thoroughfare, the Ringstraße. These structures of everyday life and of imagination form part of a more general territory of psycho-topography in Schnitzler’s work.

Frederick Baker

The psycho-topographic territory

The function of location in Schnitzler’s work is a key concern for the Schnitzler digital edition project, as will be seen in Placing Schnitzler, our special 2019 edition of the journal Austrian Studies. It is indicative that two of our works – Der Weg ins Freie and Das weite Land – have topographical titles. Schnitzler’s writings are insistently concerned with space, both actual and metaphorical, and how human agents occupy and find their way around it. Or indeed seek to get out of it – the title Der Weg ins Freie marks a narrative with an almost virulent attachment to travel, both voluntary and involuntary, actual and figurative.

In the case of Das weite Land, the wide domain of the title is explicitly a metaphor for the human soul: ‘Die Seele ist ein weites Land’; as the saying, echoed in the play, has it. There is also an operative tension between the senses of wide or vast and distant, suggesting that the soul or psyche, this ostensibly most intimate part of human existence, could be at a distance from it, remote. But the wide or far domain can also be seen as a reference to the way in which the drama extends beyond Vienna, first to the dormitory town of Baden bei Wien, then to some of the further reaches of the Empire in the third Act – set, like Fräulein Else, in the Dolomites – and indeed beyond, through a set of references to international travel. Space always has symbolic value here, especially in its often ironically constrained relationship to the idea of escape from the everyday conditions of life. While many other Schnitzler texts are, of course, set more fully in Vienna itself, the city also emerges as a kind of psycho-topographic ‘wide domain’. It is a place of many, often contradictory locations – ‘geheime Bezirke’; or secret districts, as they are called in Traumnovelle – cast between the familiar and the foreign or uncanny.

A new turn of the circular traffic takes us from the wide or distant domain of the human soul to the narrow confines of the human body, as Annja Neumann discusses in one of the hotspots in the Praterkasperl Theater in Vienna’s famous amusement park, where a plethora of little stages and booths acts as a projection space for the psyche of the spectator and the merry-go-around becomes an emblem of a broader circularity. Many of Schnitzler’s stories and dramas negotiate human-ness through bodily activity and its obstruction. Schnitzler’s scandalous comedy ‘Zum großen Wurstel’ (‘The Great Wurstel’ or ‘The Grand Guignol’), for example, explores the entangled embodiment between humans and machines by using wires to manipulate human actors and their physicality. Just as what Schnitzler calls his escape into the ‘puppet-like’ provides a projective extension of theatre’s experiments with what it means to be human, the psycho-topographical logic of the spheres extends our visual field from the stage area to 360-degree panoramic vision, reaching from the backstage area to the auditorium. Accordingly, the audience and the theatrical machinery are brought into the panoramic picture and set in ambiguous relation with one another.

Andrew Webber

Theatrical embodiments, projections and entanglements

In his theatrical parody ‘Zum großen Wurstel’ Schnitzler sets up an experiment with place and space which is extreme in its theatricality. Place and space are explicitly produced through material bodies and their interactive movements in this dramatic laboratory. Bodily practices, both on stage and in the stalls, co-create an immersive experience and a space which is defined through constant acts of boundary crossing. Here characters who cross the borders between the stage area and the auditorium, and between different textual domains, create a model for the fluid space of the Schnitzler Sphere. Borders and connecting lines between Schnitzler’s imagined world, the author’s life and the realities of today emerge and are dynamically constituted by the ways in which we move through them.

Illustrator Berta Czegka framed the boundaries between the supposedly fictive world and the allegedly real audience through a conventional pictorial frame in her stage drawing for ‘Zum großen Wurstel’, which can be seen in the Praterkasperl sphere. Inspired by Czegka’s illustration of the stage set and the constant boundary-crossings of Schnitzler’s characters, the Schnitzler Spheres adapt the viewing frame of this picture to expose boundary-making practices. This operates in a similar way to the viewing stations of the Kaiserpanorama. And yet the spherical logic inverts the location of the spectator by projecting us, in the role of experimental topographers, into the centre of the spectacle.

As we navigate through a sphere the dramatic viewing apparatus provokes a continuous changing of perspective. We start by watching a Punch-and-Judy show in the Praterkasperl sphere, before – turning through 180 degrees – the audience takes centre-stage. In the Anatomical Theatre sphere our viewpoint is elevated to a bird’s-eye perspective, which draws our attention to Emil Zuckerkandl’s Anatomical Atlas in the centre of the room, this a familiar view and location for Schnitzler during his time as a medical student. His medical drama Professor Bernhardi explores the disposition of bodies in these medical places as they are subjected to institutional power. The case of Bernhardi, which is enacted in Schnitzler’s fictive hospital, heard in court and debated in parliament, takes us through some of the key institutional spaces of the ‘wide domain’ of the Habsburg monarchy. The grand hotel is another such space, where the personal and socio-political dynamics of the monarchy are played out. Moving out of Vienna to the recreational space of the Semmering we can take a seat in the lobby of the Südbahnhotel sphere and observe the behaviour of guests as they enter this social stage, as Schnitzler used to do for hours. Above all the viewing frame of the spheres creates a play-within-a-play structure in its exploration of the interplay between the social arena and the theatre.

This projection of life into theatre takes us full circle to Schnitzler’s comedy ‘Zum großen Wurstel’ and a new performance space or booth, a marionette theatre, surrounded by visitors to the so-called Wurstelprater. Here he creates a metatheatrical event by doubling both the audience and the stage set. It is the boisterous heart of the Viennese amusement park which was as familiar a place of popular cultural recreation to Schnitzler and many of his characters as it continues to be today. A particular scene which contributes to one of Schnitzler’s most radical dramatic experiments is one of enormous, if ambiguous physicality.

Wrestling scene in the Cambridge production of

Wrestling scene in the Cambridge production of'Zum großen Wurstel', 2019

In his burlesque fairground comedy, a ‘Ringkämpfer’ or wrestler, a well-known type from the Viennese amusement district, enters the stage of the bourgeois theatre and fights with a marionette. Here the characters are not only crossing borders between low and high culture, the wrestling scene also challenges boundaries between humans and machines as components of theatrical performance. This, in turn, reflects upon the entanglement of the human in the broader apparatus of theatre as a paradigmatic social institution, and the apparatus of society – as theatrum mundi.

Annja Neumann

Usage

Click the circles in the overview diagram to enter into the space of the spheres. Within a sphere, use your mouse to drag the viewpoint around and find out more by clicking on hotspots, marked by a square.

From within a sphere, you can always click the little diagram icon in the top middle of the page to return to the overview diagram.

Design and Development

Visual design, interaction design and development by Lost in the Garden. Handcrafted in Vienna

Credits

Concept and Direction: Dr. Frederick Baker (University of Cambridge & Media Europa)

Director of Literary Content: Dr Annja Neumann (University of Cambridge)

Literary Editor: Professor Andrew Webber (University of Cambridge)

University Library webmaster: Hal Blackburn (University of Cambridge)

Graphic designer: Raimund Schuhmacher (Lost in the Garden)

Interactions design: Simon Wallner, Matthias Maschek (Lost in the Garden)

360 photos: Thomas Bredenfeld

Additional Graphics: Gabriel Pall

Early development:

Professor Alexander Pfeiffer (Donau Universität, Krems)

Martin Moellner, Markus Kallinger, Roman Winkler (Donau Universität, Krems)

Production: Sandra Fasolt (Media Europa)

Research:

Dr. Rudi Risatti, Österreichisches Theater Museum, Vienna

Mag. Rita Czapka, Burgtheater Media Archive, Vienna

Professor Dr. Michael Pretterklieber, Medizinische Universität, Vienna

Special thanks to Südbahnhotel, Semmering

Elis Veit & Thomas Ettl, Original Wiener Prater Kasperl

Preferred citation:

Frederick Baker, Annja Neumann and Andrew Webber, Schnitzler: Story: Spheres, an interactive digital 360-degree panorama

(Cambridge: CUL, 2020), URL: http://schnitzler-spheres.lib.cam.ac.uk.

Permanent link: http://schnitzler-spheres.lib.cam.ac.uk

Lesetext

Lesetext